In mathematics, the Poincaré inequality is a result in the theory of Sobolev spaces, named after the French mathematician Henri Poincaré. The inequality allows one to obtain bounds on a function using bounds on its derivatives and the geometry of its domain of definition. Such bounds are of great importance in the modern, direct methods of the calculus of variations. A very closely related result is the Friedrichs’ inequality.

This topic will cover two versions of the Poincaré inequality, one is for  spaces and the other is for

spaces and the other is for  spaces.

spaces.

The classical Poincaré inequality for  spaces. Assume that

spaces. Assume that  and that

and that  is a bounded open subset of the

is a bounded open subset of the  –dimensional Euclidean space

–dimensional Euclidean space  with a Lipschitz boundary (i.e.,

with a Lipschitz boundary (i.e.,  is an open, bounded Lipschitz domain). Then there exists a constant

is an open, bounded Lipschitz domain). Then there exists a constant  , depending only on

, depending only on  and

and  , such that for every function

, such that for every function  in the Sobolev space

in the Sobolev space  ,

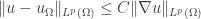

,

,

,

where

is the average value of  over

over  , with

, with  standing for the Lebesgue measure of the domain

standing for the Lebesgue measure of the domain  .

.

Proof. We argue by contradiction. Were the stated estimate false, there would exist for each integer  a function

a function  satisfying

satisfying

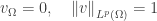

.

.

We renormalize by defining

.

.

Then

and therefore

.

.

In particular the functions  are bounded in

are bounded in  .

.

By mean of the Rellich-Kondrachov Theorem, there exists a subsequence  and a function

and a function  such that

such that

in

in  .

.

Passing to a limit, one easily gets

.

.

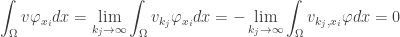

On the other hand, for each  and

and  ,

,

.

.

Consequently,  with

with  a.e. Thus

a.e. Thus  is constant since

is constant since  is connected. Since

is connected. Since  then

then  . This contradicts to

. This contradicts to  .

.

The Poincaré inequality for  spaces. Assume that

spaces. Assume that  is a bounded open subset of the

is a bounded open subset of the  -dimensional Euclidean space

-dimensional Euclidean space  with a Lipschitz boundary (i.e.,

with a Lipschitz boundary (i.e.,  is an open, bounded Lipschitz domain). Then there exists a constant

is an open, bounded Lipschitz domain). Then there exists a constant  , depending only on

, depending only on  such that for every function

such that for every function  in the Sobolev space

in the Sobolev space  ,

,

.

.

Proof. Assume  can be enclosed in a cube

can be enclosed in a cube

.

.

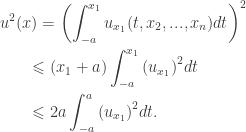

Then for any  , we have

, we have

.

.

Thus

.

.

Integration over  from

from  to

to  gives the result.

gives the result.

The Poincaré inequality for  spaces. Assume that

spaces. Assume that  and that

and that  is a bounded open subset of the

is a bounded open subset of the  -dimensional Euclidean space

-dimensional Euclidean space  with a Lipschitz boundary (i.e.,

with a Lipschitz boundary (i.e.,  is an open, bounded Lipschitz domain). Then there exists a constant

is an open, bounded Lipschitz domain). Then there exists a constant  , depending only on

, depending only on  and

and  , such that for every function

, such that for every function  in the Sobolev space

in the Sobolev space  ,

,

,

,

where  is defined to be

is defined to be  .

.

Proof. The proof of this version is exactly the same to the proof of  case.

case.

Remark. The point  on the boundary of

on the boundary of  is important. Otherwise, the constant function will not satisfy the Poincaré inequality. In order to avoid this restriction, a weight has been added like the classical Poincaré inequality for

is important. Otherwise, the constant function will not satisfy the Poincaré inequality. In order to avoid this restriction, a weight has been added like the classical Poincaré inequality for  case. Sometimes, the Poincaré inequality for

case. Sometimes, the Poincaré inequality for  spaces is called the Sobolev inequality.

spaces is called the Sobolev inequality.

between two metric spaces to obtain a new function

enjoying certain properties. I am interested in the following three properties:

and

we mean metric spaces with metrics

and

respectively.

is only assumed to be continuous. In this scenario, there is no hope that we can extend such a continuous function

to obtain a new continuous function

. The following counter-example demonstrates this:

and let

be any continuous function on

such that there is a positive gap between

and

. For example, we can choose

is monotone increasing, we clearly have

of

cannot be continuous because

will be discontinuous at

. Thus, we have just shown that continuity is not enough. For this reason, we require

to be uniformly continuous.